Elevating Culinary History: The Impact of Diane M. Spivey’s Work

Fig. 1: Culinary historian Diane M. Spivey.

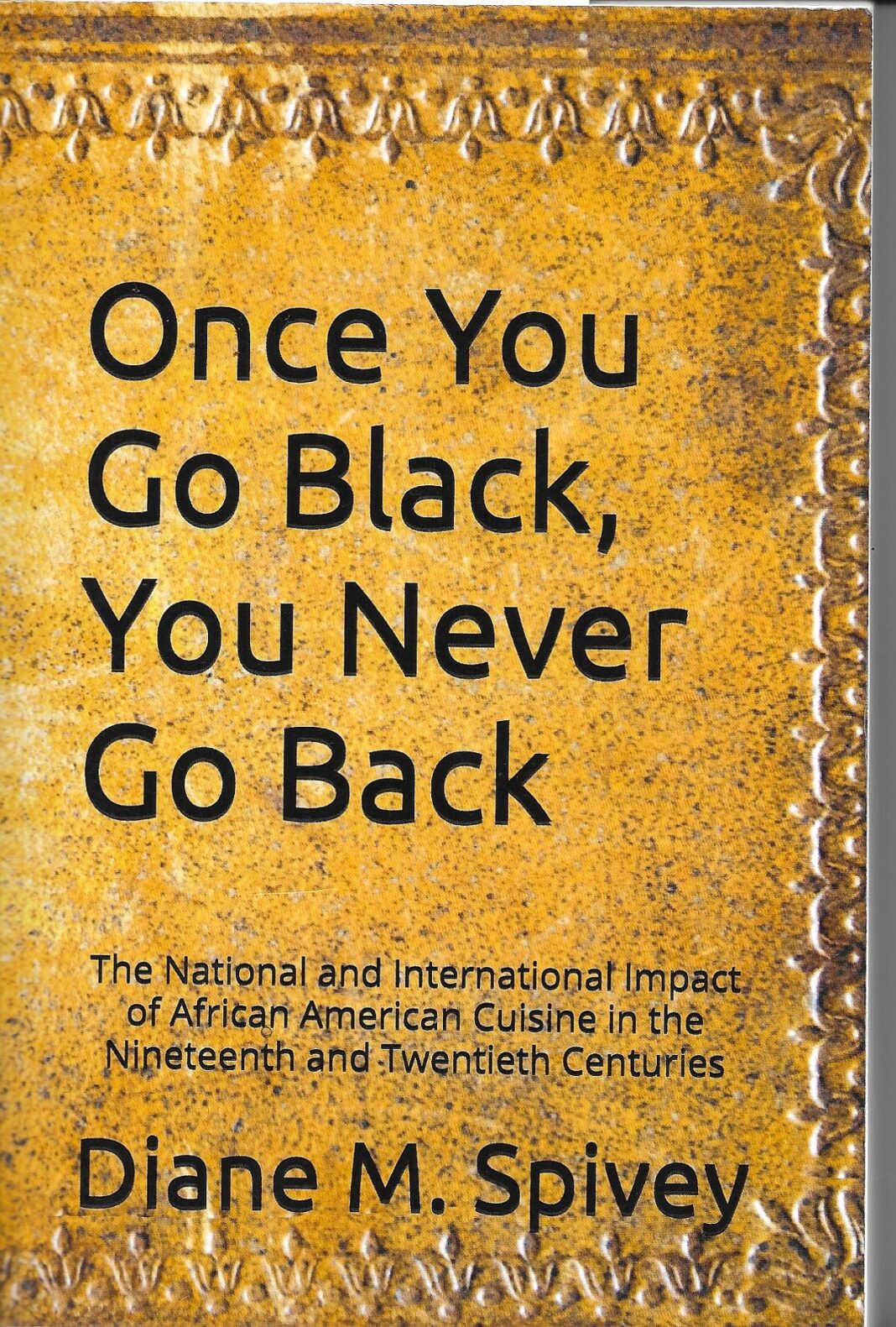

Culinary history is often portrayed through a narrow lens that marginalizes significant contributions from diverse cultures. Diane M. Spivey, a prominent culinary historian, seeks to challenge this perspective with her influential book, “Once You Go Black, You Never Go Back: The National and International Impact of African American Cuisine in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.” Through her works, Spivey highlights the rich heritage and substantial influence of African American cuisine, a narrative that has historically been overlooked.

Correcting the Culinary Narrative

Diane Spivey’s recent publication aims to rectify misconceptions and omissions in the culinary story of America. In her earlier work “At the Table of Power: Food and Cuisine in the African American Struggle for Freedom and Justice,” she meticulously details how traditional culinary histories often erase Black contributions, leading to what she terms “culinary apartheid.” This suppression of Black culinary achievements, according to Spivey, enables a form of cultural theft that credits others for innovations pioneered by African Americans.

Spivey’s original manuscript for “At the Table of Power” exceeded 1,000 pages, forcing her to split it into two volumes. The second volume, “Once You Go Black,” delves deeper into the successes of Black individuals in the U.S. food industry during eras marked by adversity, such as slavery, when legal restrictions were specifically designed to impede their progress.

Unearthing Stolen Recipes

One glaring issue that Spivey tackles is the pervasive appropriation of Black culinary artistry. She shed light on historical figures like Joseph Lee, a 19th-century restaurant owner who invented patented dough kneading and bread crumbing machines, revolutionizing industrial bread-making. Lee catered to elite clientele, including presidents, but remains largely unrecognized in traditional culinary narratives.

Spivey also brings attention to the work of Sarah Victor, a pastry chef at New York’s famed Algonquin Hotel. Victor crafted delectable desserts, yet her recipes were published under the hotel’s name in the 1942 cookbook “Feeding the Lions: An Algonquin Cookbook” without any acknowledgment of her contributions. Spivey poignantly illustrates the injustice inherent in such omissions: “Here we have culinary masterpieces with no attribution to the innovator.”

Global Culinary Influence

The influence of African American cuisine extends far beyond U.S. borders. Influential figures like Louis Mitchell, a jazz drummer, popularized African American-style meals in both Paris and the U.S. Similarly, Josephine Baker showcased Black culinary arts internationally through her successful restaurant, Chez Josephine, which served African-inspired dishes amidst a vibrant cultural scene.

Baker’s restaurant, opened in 1926, was an immediate success and highlighted the fusion of African American tastes with European culinary techniques. She featured dishes that paired soul food staples with French haute cuisine, underscoring the versatility and richness of African American culinary traditions.

Broader Implications of Culinary Heritage

Despite their culinary successes, many African American chefs faced societal resistance and familial disdain towards cooking as a profession. Spivey articulates this historical stigma, especially as families distanced themselves from roles associated with domestic servitude, a legacy rooted in slavery.

This societal shift posed challenges for subsequent generations, as culinary opportunities became increasingly dominated by elite white chefs trained in traditional French dining. Spivey notes, “As the 20th century progressed, cooking became part of the entertainment industry, with whites positioning themselves as culinary authorities.”

Challenging Cultural Restriction

Spivey doesn’t propose merely seeking acknowledgment from mainstream culinary institutions; she stresses the importance of self-affirmation within the African American community regarding their culinary history. She fervently argues against labeling African American cuisine solely as “soul food,” a classification she sees as limiting and reductive—a form of “cultural and culinary shackling.”

Her viewpoint is clear: African Americans should recognize and celebrate their culinary excellence autonomously. She emphasizes, “We cannot afford to depend on others to acknowledge us. We must do this ourselves.”

A Call for Recognition

With “Once You Go Black,” Spivey aims to educate a diverse audience, from high school students to culinary professionals, ensuring a more accurate understanding of American food history. By illustrating the depth and richness of African American cuisine, she strives for a future where such contributions are recognized and celebrated in their own right.

Her commitment to rewriting cultural narratives challenges the industry to rethink its approach to culinary legacy, pushing against historical biases. By sharing stories of resilience and success in the face of challenges, Spivey is not just preserving history; she is actively reshaping the future of culinary acknowledgment.

Fig. 2: Recipe for “Harlem Nights in Montmartre Brown Sugar Ice Cream.”

These endeavors not only contribute to the broader discourse surrounding food and culture but also provide healing and recognition for generations whose culinary gifts have been historically marginalized. From honoring celebrated figures to reclaiming recipes, Spivey’s work resonates with a spirit of empowerment, galvanizing a renewed appreciation for the profound depths of African American culinary tradition.