Essential Lessons from “The Capital of Slavery”

Dr. Gerald Horne’s recent work, The Capital of Slavery: Washington, D.C., 1800-1865, provides a riveting exploration of how Washington, D.C., served as the epicenter of a nation whose political and economic foundation was built upon the enslavement of African people. Horne asserts that slavery was not a peripheral issue but rather the “main event,” pivotal to the capitalist structure of the United States.

The Legacy of Slaveholding Leaders

Horne’s title refers to the legacy of prominent American figures who were deeply entrenched in slaveholding. Ten U.S. Presidents prior to the Civil War, including foundational leaders such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, were wealthy slave owners. This pattern extended into the judiciary: twenty-six of the first thirty Supreme Court Justices owned slaves. Additionally, around 1,800 members of Congress were slaveholders at some point. These statistics underline how systemic slavery infiltrated the very fabric of U.S. governance.

The Constitution and Class Dynamics

The U.S. Constitution was crafted to protect property rights—a foundation crucial to capitalism—thereby prioritizing the interests of the “minority of the opulent” against the welfare of the majority. Enslaved individuals represented the most valuable form of property, valued more than all the nation’s industrial assets combined, highlighting the economic stakes of slavery.

Horne emphasizes that the Constitution functioned as a shield for the institution of enslaved labor. The United States, in its essence, functioned as a republic for rich white slave owners, fundamentally excluding the voices of non-white populations.

Reinterpreting Historical Resistance

Horne draws connections between his recent work and his earlier text, The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States, where he illustrates that many enslaved Black Americans opted to join the British forces during the Revolutionary War, motivated by the promise of freedom. This relationship between slavery and class struggle is a core theme throughout Horne’s writings, which remind readers that oppression breeds resistance.

Slavery as Class Exploitation

One critical takeaway from Horne’s work is the portrayal of enslaved Black individuals as members of the unpaid working class. By framing slavery in the context of class struggle, he aligns his analysis with that of W.E.B. Du Bois in Black Reconstruction, reaffirming that the enslaved actively resisted their exploitation.

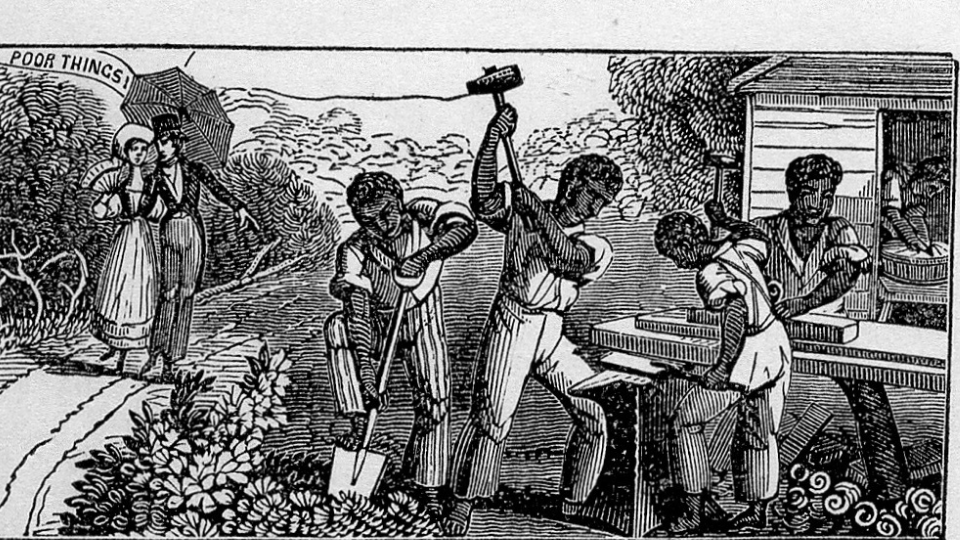

Washington, D.C.: A Hub of Slave Trade

Horne paints a vivid picture of Washington, D.C., as a major slave-trading hub, strategically positioned near Virginia, a leading slave society. He reveals the gruesome reality of “slave pens” where human beings were treated like merchandise, awaiting sale.

During the War of 1812, many enslaved individuals seized the opportunity to fight for the British, who offered them freedom in exchange for military service. This period was fraught with contradictions, illustrated in the national anthem penned by Francis Scott Key, which expresses derision for the very people in struggle against oppression.

The Colonization Movement

The narrative also touches upon the establishment of the American Colonization Society by elite political figures, aimed at deporting freed African Americans to Liberia. This initiative stemmed from a fear that liberated Black individuals could incite enslaved populations with ideas of freedom, challenging the status quo of enslavement.

Modern Implications

Horne draws a parallel between historical and modern contexts, noting that the social dynamics of race and class collaboration are still at play. He critiques the way different segments of society, including poor whites in the antebellum South and contemporary political factions, have aligned with systemic oppression for perceived benefits.

Class Struggle and Resistance Movements

Crucially, Horne posits that the systematic resistance from enslaved populations, including revolts and general strikes, significantly contributed to the decline of chattel slavery. He argues that the influence of international movements, such as the Haitian Revolution, was instrumental in shaping abolitionist efforts worldwide.

The Need for Broader Perspectives

As Horne delves deeper into the interconnectedness of capitalism and white supremacy, he compels modern activists and thinkers to reassess historical narratives. Understanding the original socio-political landscape of the United States as a slaveholder’s republic is crucial for contemporary struggles against systemic oppression.

Through Horne’s insights, contemporary debates on class, race, and socio-economic dynamics are encouraged to examine the evolution and interdependence of slavery, capitalism, and white supremacy. By fostering a nuanced understanding of these themes, activists can more effectively address today’s pressing issues in society.

Horne’s analysis presents a corrective lens through which we can scrutinize the legacy of America’s foundational myths, pushing us to advocate for a society where equity and justice replace exploitation and oppression.