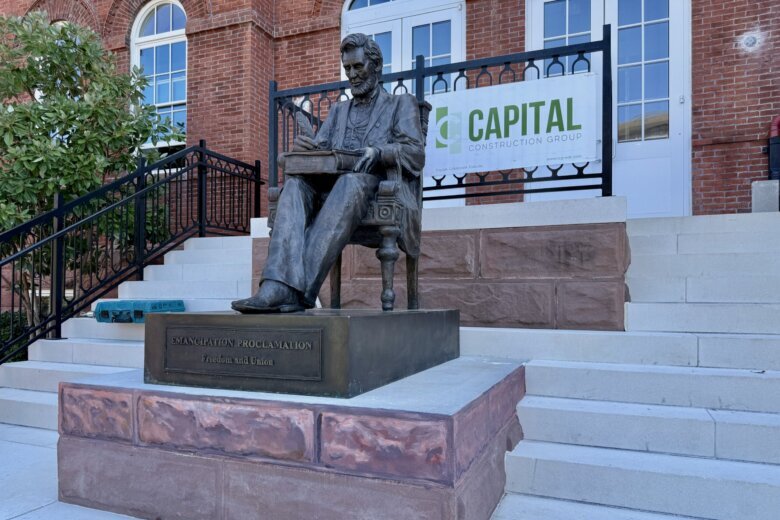

On a significant day marking the historical signing of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, a new statue of President Abraham Lincoln was unveiled outside the African American Civil War Museum in Northwest D.C. This event drew dozens of attendees, each eager to witness a tribute honoring a pivotal figure in American history. The statue depicts Lincoln in the act of signing the landmark document that would pave the way toward freedom for countless African Americans.

President Abraham Lincoln signed the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation 162 years ago this week. To celebrate, dozens of people gathered for the unveiling of a new presidential statue outside the African American Civil War Museum in D.C.

The statue serves as a reminder of Lincoln’s role in a transformative period of American history. Much like the Proclamation itself, which was a step toward freedom, the unveiling represents progress for the museum and the broader community. According to Frank Smith, the executive director of the museum, “It’s very important for us to reaffirm these notions of freedom and union, which is what this monument talks about.”

Coinciding with the unveiling is a larger narrative about the museum’s commitment to celebrating African American contributions during the Civil War. As it prepares to reopen in November following substantial renovations, the museum will feature enhanced exhibits dedicated to the U.S. Colored Troops—over 200,000 freed Black Americans who fought for the Union. As noted by retired U.S. Navy Capt. Edward Gantt, “It wasn’t until the Emancipation Proclamation that African American men were allowed to enlist in the U.S. Army as soldiers.”

At the unveiling, Gantt was among a group of reenactors who donned period attire, embodying the soldiers who once took up arms for their freedom. “When we grew up in the 20th century, we didn’t hear anything about that. We didn’t know it until the movie ‘Glory’ came out,” he reflected, highlighting a common gap in historical education regarding African American troops in the Civil War.

Fellow reenactor Bernie Siler echoed Gantt’s sentiments, referring to the forthcoming exhibits as “Glory Part Two.” He emphasized that the museum’s new displays would enlighten visitors about the often-ignored hardships faced by these soldiers, such as their lack of pay and the brutal realities of being captured by Confederate forces. “The declaration by the Confederates that they would not accept Black soldiers as prisoners, but execute them on the battlefield,” Siler explained, is a crucial aspect of this untold history. For him, wearing the Union uniform is both an honor and a responsibility. “I transport myself back and depict those men who volunteered, and because of the Emancipation, they’re able to now serve the Union army,” he shared.

Visitors to the renovated museum will encounter Marquett Milton, a historical interpreter in Union dress, who is eager to convey the important roles played by U.S. Colored Troops beyond combat. “These colored soldiers were not just fighting in battles, but they were policing towns. They were also helping recruit African Americans into the Union Army, escorting them to contraband camps, where they would also be educated,” Milton detailed, emphasizing the multifaceted contributions of these troops.

Milton’s connection to history is personal; he proudly shares about his ancestor, John Middleton, who served in the 34th Colored Infantry of South Carolina. “He served three years and survived the war,” Milton said, drawing a poignant link between the past and the present.

The museum’s reopening on November 11—Veterans Day—promises to be a significant event. Attendees will witness a solemn tribute as the names of all 209,145 U.S. Colored Troops are read aloud, etched in remembrance on the Wall of Honor adjacent to the Spirit of Freedom statue. This ceremony will not only honor the sacrifices made by these soldiers but also reflect the ongoing journey of recognizing and celebrating African American history in the United States.